Technical

INSIGHT: Freeze dates and cost cap concerns – How do you build a Formula 1 chassis?

Share

When we talk about risk in Formula 1, it’s usually the brave driver keeping his foot down through Campsa, or the strategist rolling the dice on a late pit-stop. Rarely do we think of the production controller back at the factory as the high-stakes gambler – but in the cost-cap era, increasingly that’s the case.

These winter months are, counter-intuitively, the busiest of the year for F1 teams. Everybody is frenetic, from mechanics feeling their way around new cars and new pit stop kit, to marketing departments frantically trying to get that big deal signed – but busiest of all are the manufacturing operations.

READ MORE: Anatomy of a pit stop: How do F1 teams service their cars in less than two seconds?

Building two all-new cars, a suite of aerodynamic options and sufficient spares is a knife-edge challenge with a non-negotiable delivery date.

Customarily, the teams would contract-out work to get through this pre-season production logjam… but in the modern era, a more cost-conscious pit lane isn’t quite so willing to pick up the phone to Composites-R-Us. They’ll still use those suppliers to a certain extent, but equally, will be making decisions about what they really need…

The 19-car grid in Australia last year is a good illustration of what’s at stake with these decisions. Williams’ inability to field a car in Melbourne for Logan Sargeant had shock value, though as Team Principal James Vowles explained, being short of a spare chassis was the natural consequence of having a lot to do and not enough time to do it all.

“In terms of the chassis, if you put all of your resource – everything you possibly had within the organisation on it – you could be eight, 10 weeks to pretty much get a chassis done,” he explained.

Only 19 cars started the Australian Grand Prix last year, as Williams could only field one car

“And that's by the time you get to the third chassis. It takes longer for the first ones as you get used to the process. Clearly, we don't have the whole organisation just working on that. We're working at the same time on spares and updates and trying to get the throughput.”

Vowles said at the time that Williams failing to arrive with three chassis was “an outcome from an overload within the system, the complexity of this car and the amount that we were trying to push through.

WATCH: Sam Collins' Testing Takeaways and 2025 predictions

“But in terms of the complexity of it, it's enormous: the chassis is thousands and thousands of pieces you're trying to bring together at the same time.”

Williams were not the first team to be caught out in this way: back in 2022, albeit in slightly different circumstances, Haas decided to withdraw Mick Schumacher from the Saudi Arabian Grand Prix following a qualifying crash, to ensure they had sufficient parts for Melbourne.

Indeed, most team bosses will privately concede that they start a season with a paucity of spare parts and a fair degree of anxiety.

Mick Schumacher's qualifying crash in Jeddah forced Haas to withdraw him from the race

Self-inflicted urgency

In essence, this is somewhat masochistic. Teams are more than capable of arriving at the first race with a well-stocked garage – but there are various reasons why they don’t want to.

When F1 began to cut down its winter testing cycle, the phrase in vogue was ‘aggressively late’. Every team has a design-freeze date for their launch car, generally at a point when the race team was deep into the end-of-season flyaways.

READ MORE: Meticulous precision and show-stopping designs – How do you paint a Formula 1 car?

Every extra day spent working on the launch car design (hopefully) adds extra performance to the machine – but puts the manufacturing schedule under more pressure. Add in the potential to fail a homologation test or pass it too easily (either may necessitate a re-design) and schedules become very tight.

“In the big picture, one of the fundamentals is to maximise aero development time in the wind tunnel,” says Jody Egginton, Racing Bulls’ soon to be departing Technical Director. “We’re geared-up to make sure there’s minimum compromise on the aerodynamics side, because that’s where a lot of the performance lives.

More time in the wind tunnel means less time to actually build the car...

“That impacts nearly every component. The date we want to release the chassis into the drawing office and then into production is all driven to maximise aero, followed by design time.

“That means there’s a lot of investment in minimising our production phase: the more technology and more efficiency you can get into the production side of things, the more time you can devote to aero development.”

WATCH: Boldest Innovations – The inside story on some of F1’s most remarkable feats of engineering

Investment in technology has accelerated the build process but there are hard limits for how long various elements of the car take to manufacture. However skilled the staff and however clever the automation, something like a chassis is still going to take several months to produce, and no (sensible) amount of extra resource is going to reduce that.

Rather like baking a (highly complex and multi-layered) cake, the process of laying-up carbon fibre sheets, applying heat and pressure in an autoclave, curing resins and so forth, isn’t a task that can be accelerated.

Curing composite parts in an autoclave is not a process that can be sped up

Doing more with less

Beyond optimising the manufacturing process, F1’s teams are all living with a constant urge to make do with less. This isn’t a modern phenomenon – no-one has ever had the time or the budget to make everything they want – but it’s taken on a more extreme cast with the advent of the cost-cap.

Teams want to put their money on track: spare parts sitting unused in a flight case aren’t contributing any extra performance – but manufacturing a range of aerodynamic packages or cooling options almost certainly will.

READ MORE: What is the F1 cost cap and how is it enforced?

And this is the decision teams have to make: they can go into season with an averaged-out package that will work well across the variety of early-season flyaway circuits, and carry plenty of spares, or they can make bespoke packages for the tracks they’ll visit in March and April: lower downforce for Albert Park and Jeddah; something more mid-range for Suzuka, Shanghai and Sakhir; likewise, more open bodywork for the heat of the desert, but tighter for a cool, damp day in Japan.

While F1 teams like to project themselves as risk-taking, seat-of-the-pants ultimate performance outfits, the reality is that they tend to be relatively conservative, and thus the safe option of a one-size-fits-all car, with a reasonable supply of spare parts is preferable.

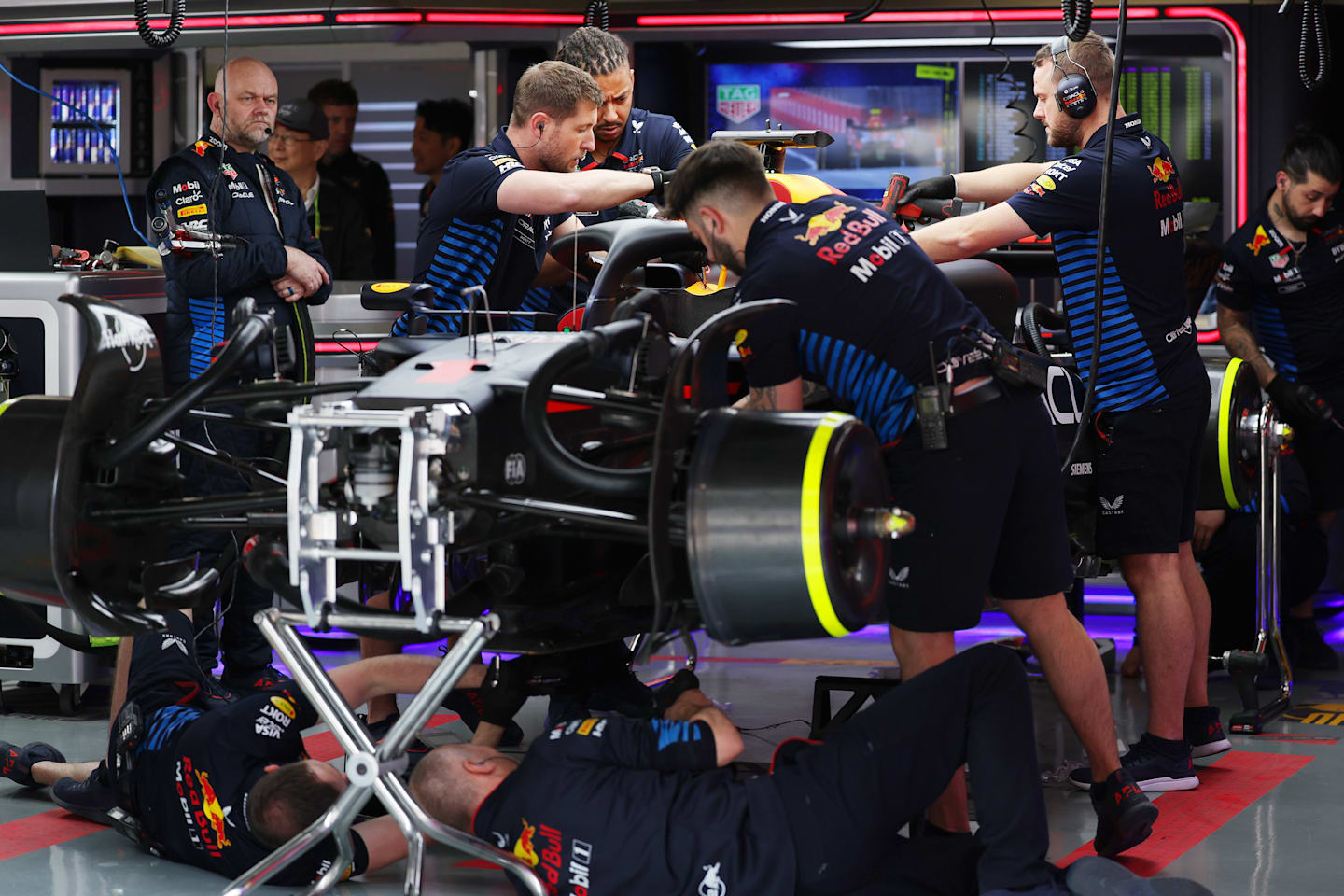

The teams don't like to have too much resource tied up in spare parts

Ultimately the team, its sponsors, and the sport in general want to see all 20 cars on track, and that isn’t something to be risked lightly. That risk is contemplated at all comes down to how incredibly, incredibly tight the F1 grid is at the moment.

The qualifying field spread across 2024 between fastest and slowest teams was frequently under a second: the extra tenth gained from being able to pick the right aero package for the track and the prevailing conditions can easily make the difference between elimination and progress, and is often worth a couple of grid positions. High risk currently equates to high reward.

WATCH: Tech Talk Retro – How some of the most iconic cars in F1 history changed the sport

“We're very focused on performance – but I'd like to think we find a good compromise,” says Egginton. “We have a certain level of stock that we're comfortable with but with budget cap, you can't give yourself margin. And we make sure we achieve that.

“Typically, we wouldn't come to an event without having enough spares – but everyone's interpretation of what ‘enough’ constitutes, will be different. If we’re bringing an aero update, for instance, the baseline plan is between three and four sets, depending on what the parts are.

TECH TALK – Beyond repair: how teams and drivers deal with crashes

“For instance, if we were taking a rear wing or new suspension to Monaco [where there exists a higher-than-average probability of crash damage], it’s four sets, end of story – but somewhere else, it might be three sets.”

2025 will be a very interesting year in this regard. With technical regulations largely unchanged from 2024, and with a revolutionary upheaval due for 2026, there’s a strong possibility that some teams will choose to retain their 2024 mechanical layout and only evolve their aerodynamic package.

It’s usually the case that the field closes-up with stable regulations and that effect is likely to be magnified in 2025. In the past, teams further back in the pack would be more likely to take a risk in order to pick-up performance, whereas front-runners, expecting to score frequently and heavily, would be more inclined to ensure both cars were available.

But given how very tight things were between the top four teams at the end of 2024, and given the situation is unlikely to be much different through 2025, any small performance advantage that can be gleaned will be more precious than ever.

TECH TALK – 2026 Regulations Explained | Crypto.com

Longer lasting cars

Another way in which teams are keen to get more bang for their (finite) buck is by extending the life of their components – though this is influenced as much by the logistics of the modern calendar as it is by the strictures of the cost-cap.

The two-race cycle for car components has been in place for many seasons. It doesn’t necessarily mean everything has a design life of two races, rather that many of the parts and assemblies are designed to operate for two consecutive race weekends (approximately 1200km) before undergoing a round of non-destructive test and inspection – typically x-rays, dye-penetrant inspection or ultrasound – before being cleared for use again.

MUST-SEE: Get an enticing behind-the-scenes look at Apple Original Films' upcoming 'F1' movie

This fitted neatly into a racing calendar built around a sequence of double-headers, but it’s a little more problematic with 24-race calendar in which triple-headers have become ubiquitous.

The usual procedures aren’t changed when races come back-to-back: the garage crews will still disassemble their cars on Sunday evening, transport them as discrete parts and sub-assemblies, and build them afresh across Wednesday and Thursday at the next track – and so the requirement to have various parts taken out of circulation hampers their effort.

At the end of every race weekend the mechanics strip down and pack away each car, ready for the next Grand Prix

The teams can choose to carry more spares, courier parts back to the factory for a quick turnaround, find local testing labs, or, where portable equipment will do the trick, bring their quality control staff out to the track.

Ultimately, these extra steps will cost more and take up more time for the team. Thus, rather like a car manufacturer offering a longer gap between services, F1 teams are moving along a path to having longer life components, with the intention of building critical parts – suspension components for example – designed with a three-race interval between inspections.

It isn’t something that’s going to generate headlines, but it is another example of the teams finding shortcuts that allow them to concentrate more of their time on what they really want to do – making their cars go faster.

READ NEXT: Inside Hamilton’s pre-season testing – and what it could mean for Ferrari’s hopes

RACE TICKETS - CHINA

Don't miss your chance to experience the thrills of Shanghai and the first F1 Sprint of the season...

DISCOVER MORE...

IT'S RACE WEEK: 5 storylines we're excited about ahead of the 2025 Chinese Grand Prix

POWER RANKINGS: Who tops our first leaderboard of the season after a wet and wild Australian GP?

TECH WEEKLY: Has McLaren’s secret weapon for the 2025 season been revealed?

Who to watch out for from the 2025 F1 ACADEMY grid as the series returns in China

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

TechnicalF1 Unlocked TECH WEEKLY: Has McLaren’s secret weapon for the 2025 season been revealed?

News Sainz felt ‘more nervous than when I’m in the car’ as he opens up on vital strategist role at Australian GP

Live Blog AS IT HAPPENED: Follow all the build-up ahead of the Chinese Grand Prix weekend

News Brown hails ‘unbelievable’ Norris drive and ‘perfect’ McLaren strategy after season-opening victory in Australia